The maven of music theory in Music City

Dr. Jenny Snodgrass brings research expertise and passion for students to the School of Music.

Janel Shoun-Smith |

The dean of the George Shinn College of Entertainment & the Arts (CEA) likes to say that Dr. Jenny Snodgrass “sees things that are good and works to make them great.” That has certainly been the case in the personal life of Lipscomb’s new academic director for the School of Music.

As an opera singer who has studied the form since she was seven years old, Snodgrass turned a stint on vocal rest after an injury at the age of 21 into an academic career that has produced awards, grants, textbooks used at Juilliard and Eastman schools of music and a quarterfinal finish for the Grammy Foundation Music Educator Award.

“This school is about to turn up to 11!” she gushes about Lipscomb’s School of Music, which has grown from 35 to 150 majors over the last six years and has produced students who have been called on to perform with famed tenor Andrea Bocelli, orchestrator and musician Cody Fry and headliner Colton Dixon.

“It’s something to be in a school where people have Grammys and are out doing amazing things,” she said.

Snodgrass came on board at Lipscomb in fall 2022 and has already jumped into teaching music theory courses, a presentation, her new chapter in the forthcoming Oxford Handbook for Public Music Theory; a one-on-one music analysis project with two music students (one classical and one commercial), and the transition of the open source academic journal she edits, Journal of Music Theory Pedagogy Online, to Lipscomb’s digital platform.

As a 17-year, tenured professor at Appalachian State University with three textbooks, Outstanding Professor and Outstanding Teacher awards and studies involving both pedagogical and theoretical research published in numerous journals, she was an obvious choice to bring her “good to great” attitude and apply it to research in the CEA.

“I think sometimes research in the arts is kind of confusing because it’s not necessarily a book. It can be an article or a conference presentation, but it can also be the research that you do to direct the show or to produce a film or to get a recital together,” said Snodgrass, who has been appointed to Lipscomb’s University Research Council. “Every single decision we make is based on understanding cultural context in history.”

While a costume designer may need to understand the culture and time period of the dramatic work or a pianist may need to analyze the musical structure of a piece, as a music theorist, Snodgrass has focused her academic works on bringing her discipline to today’s students in a way that both classical and commercial undergraduate students can relate to.

“This chapter that is coming out in the Oxford Handbook is important to me because it speaks to people about music in a way that welcomes everybody to the table,” she said. “I want to talk about it in a real conversational way. I think we’re at a point in education where students want to know, ‘How do I relate to that?’”

True to form, Snodgrass’ approach to her academic scholarship was forged through taking a good thing and making it great. Around 2009 she was asked to teach theory to Appalachian State music industry students. Dissatisfied with her own application of music theory knowledge to the commercial side of the discipline, she expressed her desire to do better and was awarded a sabbatical.

She came to Music City to “live in” Nashville studios for a semester. “I listened to how they talked. I watched what they did and listened to how they created. I went to songwriter nights. I sat in with and talked to engineers and interviewed people,” she said.

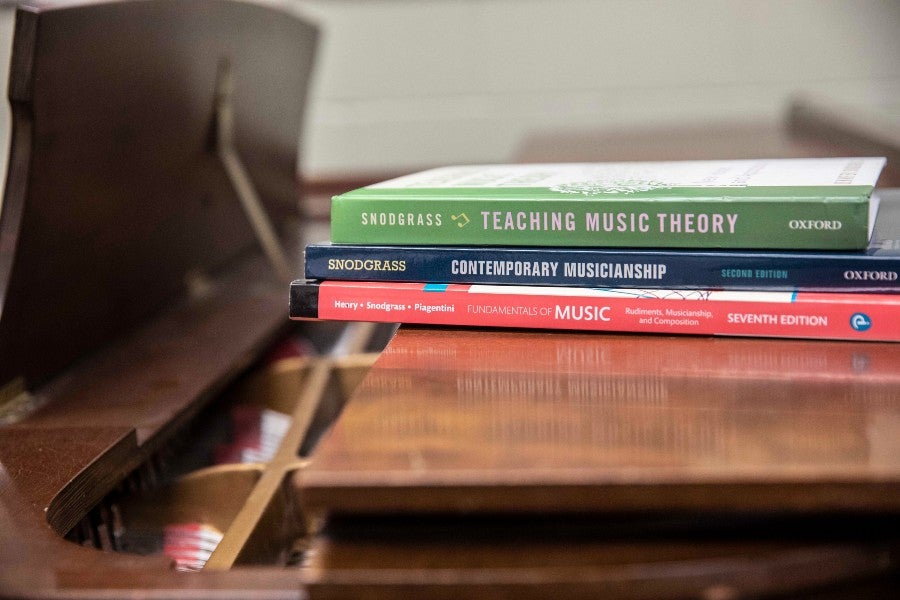

The result was a book called Contemporary Musicianship, printed by the Oxford University Press and now in its second edition. It is a music theory textbook for both classical and commercial styles and includes interviews discussing how artists, managers and producers use music analysis in their writing, listening or in the field in general.

During that process, she met and interviewed Pat McMakin, who was then a music engineer at Belmont University and is now lead engineer at Ocean Way. Snodgrass featured him in both the first and second edition of Contemporary Musicianship and recruited him to co-author her latest chapter in the Oxford Handbook. McMakin has come to the Lipscomb campus to co-present with Snodgrass and to speak to students in classes.

As part of her continuing efforts to understand the aural and theory skills that the 21st century musician needs, Snodgrass continually talks with engineers, writers, composers and artists, not only for her own research, she notes, but also for Lipscomb students’ connections for their future careers.

She has plans to involve a team of 10 to 20 students in producing the third edition of Contemporary Musicianship during 2024-2025.

“When you’re dealing with modern pop, country and Christian music, you’ve got to pay for a lot of copyrights, so this experience will not just be music analysis. It will be about the business of getting copyrights, which every music student should know about,” said Snodgrass.

As a passionate supporter of undergraduate research, Snodgrass advocates providing real-world projects for college students of any age. “Instead of saying, ‘What would it be like?’, let's really do it. For real,” she says.

Snodgrass repeated her on-site approach in information gathering for her book, Teaching Music Theory: New Voices and Approaches, published by Oxford University Press in 2021. For this book, which is used as a text at Juilliard and Eastman, she traveled to 19 states to watch how people taught music theory.

Even in her new administrative role at Lipscomb, Snodgrass is still teaching music theory courses. “I need to know what’s happening in my students’ lives, because it impacts my research and vice versa,” she said.

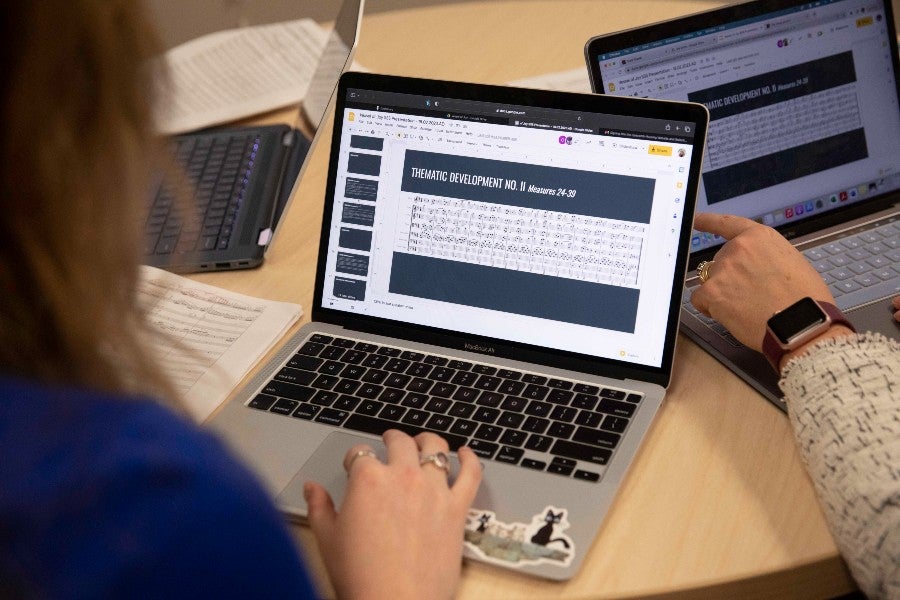

In her first semester, two students were so inspired as they learned about music analysis that they launched an independent study with Snodgrass to take a deeper dive into an orchestral work and then present their analysis at the April Student Scholars Symposium.

Snodgrass hopes to send Lipscomb undergraduates to the National Conference on Undergraduate Research (NCUR) in the future.

“They have such open minds, and they want to understand why and how something works,” she said of undergraduate students. “These students question everything, and we should say, ‘Let’s take this next step and try to figure out what’s going on here. Let’s dissect it a little bit.’ It also says to them, ‘I know you can handle this.’ Undergraduates are so capable of so many things,” she said.

“Because of the type of school we are, this is a safe place to ask the questions, and to get the mentorship to create independent thinkers. Independent thinkers are just going to be so productive in society when they ask questions and think of new ideas. Yeah, I love undergrads.”

In addition to her books, Snodgrass has written several academic articles and chapters discussing her specialty topic: how to integrate commercial and classical music together in the classroom, published in the Oxford Handbook, the Routledge Companion to Music Theory Pedagogy and the Journal of Music Theory Pedagogy, among others.

When Lipscomb called, she immediately recognized its School of Music as a place that practices the same blended philosophy. “There’s classical music going on here. There’s commercial music going on here, and both are valued. I knew this was a place where I could thrive,” she said.

And as a bonus: “I don’t have to travel back and forth from Boone, North Carolina, to Nashville anymore!”