Getting a clue through chemistry

Biochemistry major uses summer internship and independent research to discover a way to make fingerprints on receipts visible longer.

Janel Shoun-Smith |

In summer 2022, Anna Froemming, junior biochemistry major from Milwaukee, Wisconsin, worked all summer long as an intern at the Tennessee Bureau of Investigation’s latent fingerprint unit, but those two months only sparked her interest in doing and learning more.

“I saw how they process evidence and the different techniques they use for hard surfaces versus paper, and the like,” said Froemming. “They are always looking at new ways to process evidence, and while I was there, a new article was published about processing fingerprints on thermal paper (the paper used for receipts). They asked me to experiment with it and see if I could get it to work.”

She did get it to work by combining zinc and nitric acid to produce nitrogen dioxide fumes. The print developed with a reddish-brown color. However, the print is only visible for a couple of minutes, Froemming said.

She left her internship wanting to know more and teamed up with Dr. Brian Cavitt, professor of chemistry, who said: “When a student comes to a professor with a research question, professors need to do all they can to help,” Cavitt said.

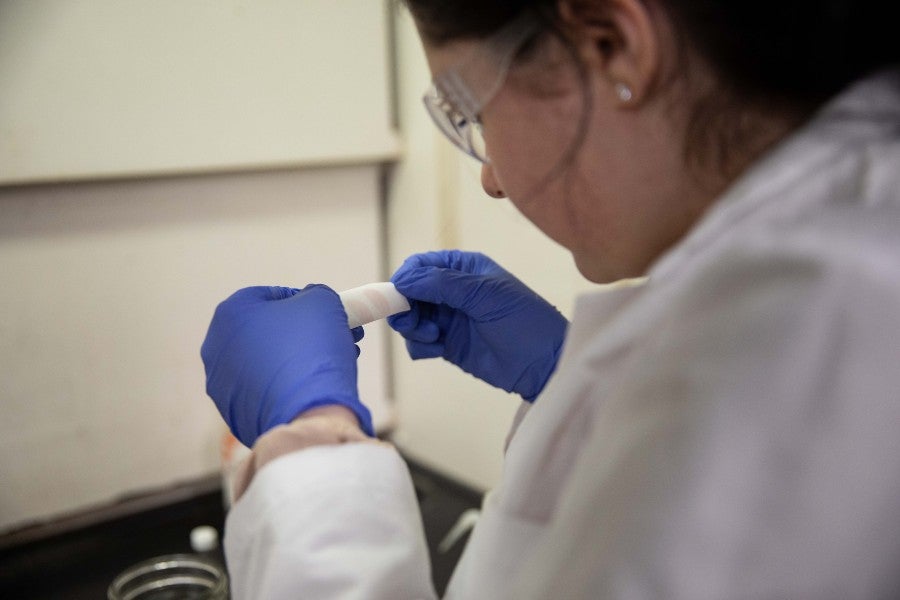

Froemming placed thermal paper with fingerprints on them in a jar with nitrogen dioxide fumes, to make the fingerprint visible with a reddish brown color.

The pair developed an experiment to test three ways to make the fingerprint image last longer on the thermal paper: immediately coating the print with a solution of paraffin wax, olive oil or PEG400 which is used in biological applications.

The PEG400 basically washed the print off, said Froemming. The olive oil worked better but left spots on the print, and the paraffin wax worked best, defining the print better and making it visible for up to a week, with some slight fading.

Froemming says she is looking forward to making a difference in the world by helping to solve crime. She pursued additional experiments this past spring because “I just feel passionate about it. I’m not looking to receive anything from it, but I just want to know a way to fix those prints.

“I think this project taught me how to have a broader perspective and to implement things I have learned in class,” she said. “In class, we learn how metals and acids interact to create new compounds, but seeing it in a real-world application has been really cool. We had to come up with the guide and procedure to do the experiment, so I felt like I was doing something real, not just an assignment.”

Froemming found that spraying the print with paraffin wax worked best, defined the print, making it visible for up to a week with some slight fading.