Explore the Lipscomb cave system through stories and speculation

Construction experts and history enthusiasts would agree the infamous space beneath campus has a reputation larger than itself

Cate Zenzen |

With over 129 years of history, stories about Lipscomb University can be heard all over the world -- some truthful and others still up to debate. One such legend is the cave system, rumored to be beneath campus and large enough for people to have explored at one point in time. Over the years as the campus has expanded, architects, engineers, and construction professionals have discovered areas that some consider “caves,” and others disregard as mundane geology.

For generations, students have speculated about a space in the rock beneath Avalon House, the historic home of David and Margaret Lipscomb in the mid 1800s. According to Mary Nelle Chumley, manager of Avalon House since the 1980’s, the house was strategically built on top of a rock that hosted an underground spring. Spaces like these were commonly used as a source for drinking water and kept perishable items cool. Chumley said this natural cellar was very small and used by Margaret to store milk and butter.

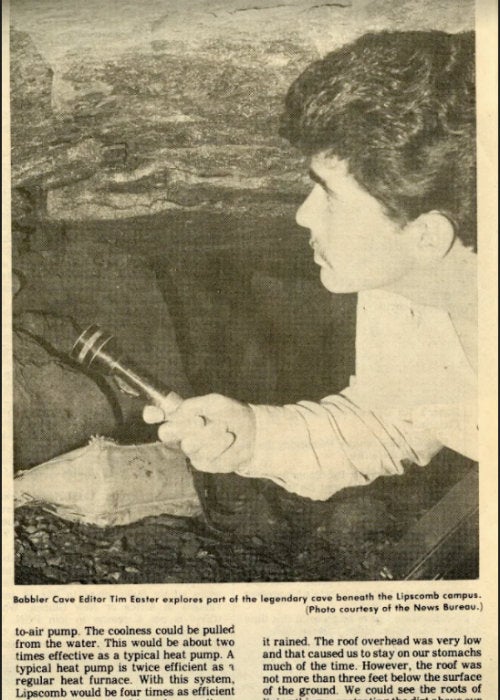

Tim Easter's 1981 photo and story exploring the space beneath Avalon House

In 1981, students from Lipscomb’s former printed student newspaper, The Babbler, investigated this space beneath the historic home. In his piece, “The cave: don’t cancel your trip to Mammoth,” student editor Tim Easter disclosed that after its use as a cellar, the opening in the rock was used to dispose of sewage and later almost converted to a direct air-to-air heat pump. Easter himself crawled into the space and wrote of it, “We never did reach a point that was any larger than six foot square. There was little room to stand up in any part that was explored. It is, however, a true cave which contains a great amount of history, speculation, and, for the most part, water.”

Mike Cochrane, an alumni of both Lipscomb Academy and Lipscomb University, grew up hearing rumors of the cave. Years later, Cochrane came back to campus with Greshen Smith and Partners to construct a parking garage on the south side of campus. In the design process of the project, the company did a geotechnical investigation of the area and found a number of voids in the ground. Nothing, however, large enough for someone to go inside.

“We found no more than a void of a few feet, which is pretty typical for this area of Nashville,” said Cochrane. “There are a lot of stories about caves, I’m just not sure how many of them are true and how much truth there is to them.”

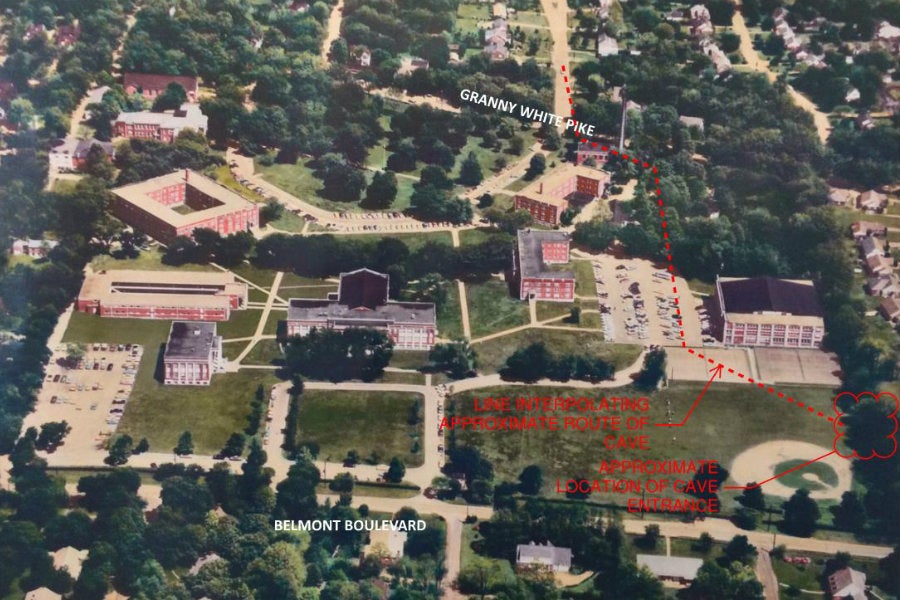

While these “voids” may be small in some areas, others have bigger evidence. Chuck Miller is an architect with Tuck-Hinton, a company that has worked on projects at Lipscomb since 1988. He said each new building needed a special foundation either using caissons or an elaborate micropile system to account for the holey bedrock. Miller suspects the system extends past Granny White Pike towards Maplehurst Avenue and is somehow tied to Brown’s Creek on Lealand Avenue.

“I believe that when the Student Activities Center was built around 1990, there may have been site work to remove or cover the entrance to the cave. There are also stories of shovels disappearing at the girls softball field that used to be located where the Ezell Center and the George Shinn Event Center are today,” said Miller.

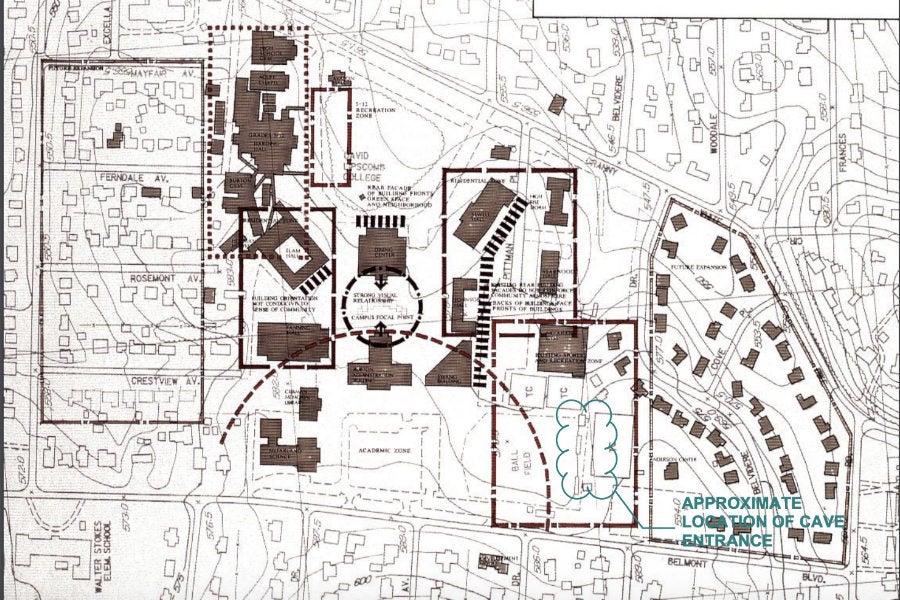

Vintage Lipscomb map with a speculated entrance to the cave system.

What Cochrane, Miller, and their colleagues discovered is not uncommon for this area. John Agee, an engineer with Terracon, has been involved with multiple projects on and around Lipscomb’s campus. Based on his work and research near the current George Shinn Event Center, he believes the area was once a groundwater injection point; part of a drainage system not uncommon in this area of the United States.

Agee had heard rumors of people entering the cave system, but nobody had located or mapped it. Terracon conducted a geophysical survey in the area and found air-filled voids, just as Cochrane had discovered.

Agee explained that the geology throughout Tennessee and Kentucky is generally karstic, meaning the limestone bedrock is susceptible to solutioning. If there is enough acidity in the rainwater, the rock erodes, dissolves, and eventually can collapse the soil covering. What Terracon found were pockets of air varying from two to five feet tall -- the result of softer limestone. Agee said these pockets are nothing to worry about, the campus is not likely to collapse into the ground, but still important to be aware of.

While most professionals believe the system to be only small voids in the earth, others continue to tell bigger tales. Chumley said one morning many years ago, she and her husband came across a collapsed sidewalk between what is now the Ezell Center and the Student Activities Center. She said a tree had dropped down into the space and only the top limbs were visible above ground. Another source from Easter’s Babbler story disclosed that the area near Avalon House once kept soldiers in the Civil War, men from both the north and the south.

As Lipscomb University continues to expand, many of these air-pockets have been filled in with concrete to support new construction. As a result, most entrances to these so-called caves have been either filled in or covered. Perhaps the reputation of the cave is bigger than the space itself, but each source would agree that, unfortunately, these natural voids are not worth exploring.